Published 28 June 2019

By threatening to withhold rare earths exports, China could be digging into this trade war with the United States.

Optics and symbolism

On May 28, the South China Morning Post reported that upon visiting one of China’s major rare earth mining and processing operations in Jiangxi Province, President Xi Jingping commented he would give priority to domestic demand over exports. Beside him was his lead negotiator in trade talks with the United States. At the same time, his top economic planning agency leaked it would not rule out using rare earths as a bargaining chip in the trade war.

The visit and Xi’s signal came just days after the Trump administration ratcheted up US tariffs on US$200 billion worth of Chinese goods followed by China’s response that it would increase in tariffs on US$60 billion worth of US goods.

When it comes to trade in rare earths, we’ve been here before. It’s a story worth unpacking as yet another cautionary tale about the perils of China’s meteoric rise to dominance in supplying the world with critical inputs, in this case the metals that lie behind today’s — and tomorrow’s — modern electronics, high-tech and advanced military applications.

Magic pixie dust in the Earth’s crust

There’s a group of 17 chemical elements on the periodic table that are classified as rare earth elements or rare earths. They can discharge and accept electrons and mix well with other elements to convey magnetism, luminescence, added strength and other key properties.

For example, neodymium helps power the magnets in hard drives and hybrid cars; praseodymium is deployed to create strong metals for aircraft engines; gadolinium is used in MRI scanning equipment; yttrium, terbium and europium are used to produce our computer, TV and device screens. As our consumer tech and industrial products become more sophisticated and new uses are discovered, demand for rare earths will only grow. Rare earths also play a key role in some of our military’s most advanced defense tools from stealth technologies to guidance systems and armored vehicles.

Not rare, but hard to harvest

The issue is not that rare earth deposits are scarce, but that they are challenging and costly to mine. Rare earths tend to be scattered rather than clustered, and bond easily with other minerals, so the elements must be separated in painstaking and costly processes that produce toxic and hazardous waste. Significant investments over years are required to get a mine and processing facility up and running and to control for environmental risks.

China’s rise to top producer, user and exporter

Although China began mining rare earths in the 1950s, the Chinese government put the capacity to mine and produce rare earths on its critical path toward economic modernization in the 1980s. Rare earths are now part of China’s Made in China 2025 plan to achieve global advantage in advanced manufacturing, high tech and green technologies.

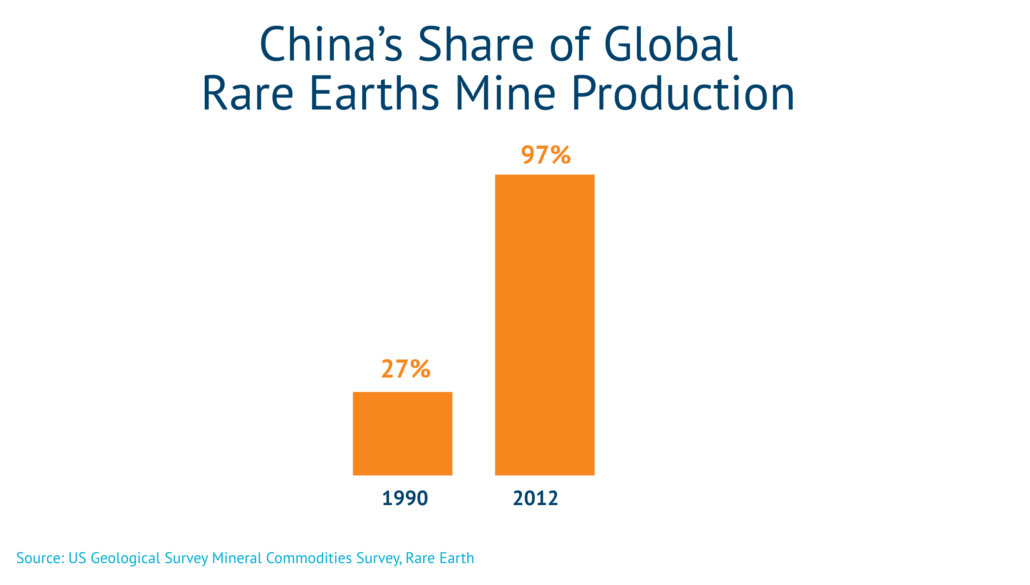

As was the case in other industries such as steel, glass, paper and auto parts, the Chinese government deepened its intervention in the rare earths sector in 1990s to ensure access to low-cost supplies for domestic producers. Government support enabled Chinese companies to ramp up mining and processing of rare earths even while operating at a loss.

As production grew, exports were encouraged through export rebates, attracting more Chinese entrants to the industry. Excess production flooded global markets, setting in motion a downward spiral in prices and profitability for producers in other countries. Between 2002 and 2005, rare earth prices dropped to historic lows, forcing most of the world’s mines outside China to close.

An overplayed hand?

Having achieved global dominance, producing over 90 percent of the world’s rare earths, China created a two-tier pricing system through a variety of export controls. According to data from the U.S. International Trade Commission, by the beginning of 2010, US importers were paying an average US$5,589 per metric ton for rare earths from China.

When China announced in July 2010 it would restrict exports of rare earths by 70 percent and impose minimum export price levels, rare earth prices surged by the fall of 2011 to US$158,389 per metric ton. By applying export duties, quotas and price floors to exports, China created a two-price system, keeping low-priced supplies for itself. US manufacturers had no alternative but to curb spending on Chinese rare earths, causing a drop in US imports.

In March 2012, the United States, European Union and Japan initiated a dispute settlement case in the WTO against China’s rare earth restrictions. Two years later, a WTO dispute panel agreed that China had violated commitments it made when it joined the WTO to eliminate dual pricing practices, certain export duties, and price controls. The panel also found China violated other aspects of other WTO agreements such as those governing the administration of export quotas. After losing its appeal, China agreed to remove quotas by December of 2014 and abandon its export tariffs by May 2015.

Damage done

Life goes on in the global economy and for industry players over the two years that WTO cases are being decided. In a 2017 National Review article, Mike Fredenburg explains what happened to the US company Molycorp that owned the Mountain Pass mine in California, which at one time was the largest producer in the world.

“In 2012, U.S.-based Molycorp, attracted to the higher prices that resulted from the Chinese government’s efforts to boost profits by restricting REE [rare earth elements] exports, made plans to ramp up domestic REE production, investing nearly $800 million in state-of-the-art mining operations in California. At the moment when the project was poised to succeed, China flooded the market with REEs just long enough to knock Molycorp out of the market. After its Chapter 11 bankruptcy reorganization, Beijing is allowing Molycorp to continue operations in China. But once again, the U.S. has no domestic REE production.”Mike Fredenburg - Founding President, Adam Smith Institute of San Diego

China lost in the WTO. But in effect, China no longer needs the trade tools that violated its WTO obligations. The Molycorp mine was bankrupt, its rare earth assets sold to a consortium of buyers that included a Chinese firm with ties to the government.

The next chapter for rare earths production and use

China’s experiments restricting exports served as a wake up call for global manufacturers and foreign governments, who are working on Plan B to China’s dominance in rare earths. Leading manufacturers including General Electric and Toyota among others have openly announced they would cultivate and support alternative suppliers while finding ways to reduce their use of rare earth elements by reengineering their product designs.

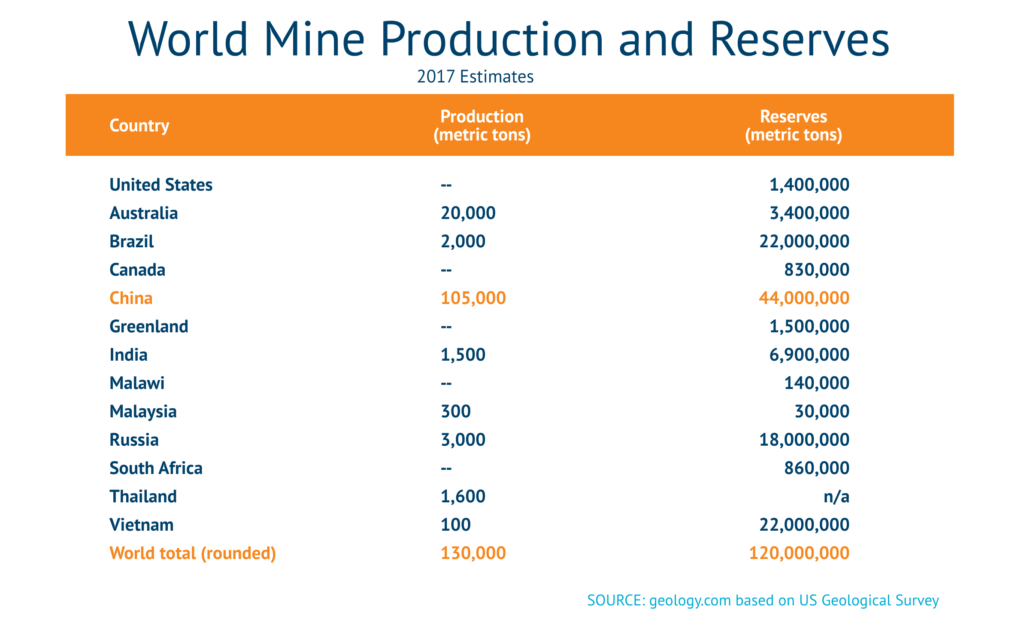

China controls 36 percent of the world’s reserves, so government agencies have stepped up efforts to find more deposits. Mining companies around the world are reevaluating old rare earth prospects for possible development and are working to develop innovative extraction techniques to achieve what fracking did for the natural gas industry in the United States.

Back to the China playbook

China will not go quietly into that good night when it comes to the advantage it created in rare earths production. Following its playbook, China is working to consolidate the number of domestic rare earths producers (all have ties to the state) and tighten oversight of resource use and production rights. No need for WTO-illegal export restrictions when state-owned or state-directed companies can directly limit their business sales with foreign buyers.

Recognizing that domestic demand could outstrip production, China is hedging its bets by purchasing rare earth resources in other countries, though not always successfully. Notably, the China Non-Ferrous Metal Mining Co. made a US$250 million bid for Australia-based Lynas back in 2009-10, but was rejected by Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board.* The Chinese state has also acquired multinational firms with science and technology assets critical to helping Chinese manufacturers move up the value chain to produce the intermediate goods and advanced technologies that use rare earths.

Meanwhile, China is stockpiling rare earths. Why?

Is the government trying to induce foreign manufacturers to produce in China? Would China withhold rare earths in the race to global use of 5G on Chinese technology platforms? Or does China simply need to ensure access to this valuable resource for the development of its own advanced manufacturing sectors?

When commenting about the role of rare earths in the trade war, a representative from the National Reform Development Commission said, “If anyone wants to use the products made from our rare earth exports to try to counter China’s development, then the people from the southern Jiangxi Communist revolutionary base would not be happy, and the people of China will not be happy.”

Perhaps the stockpiling is emblematic that China thinks the United States is trying to contain China’s economic expansion. Threatening to withhold rare earths could be China’s way of digging into this trade war with the United States.

More reading:

For context see Congressional Research Service Report, "China’s Rare Earth Industry and Export Regime"

For contemporary commentary see Stewart Paterson’s Rare Earths: The Threat of Embargo and the Clash of Systems

* Editor’s note: this sentence contains a correction from the originally posted version.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).