Published 23 April 2024

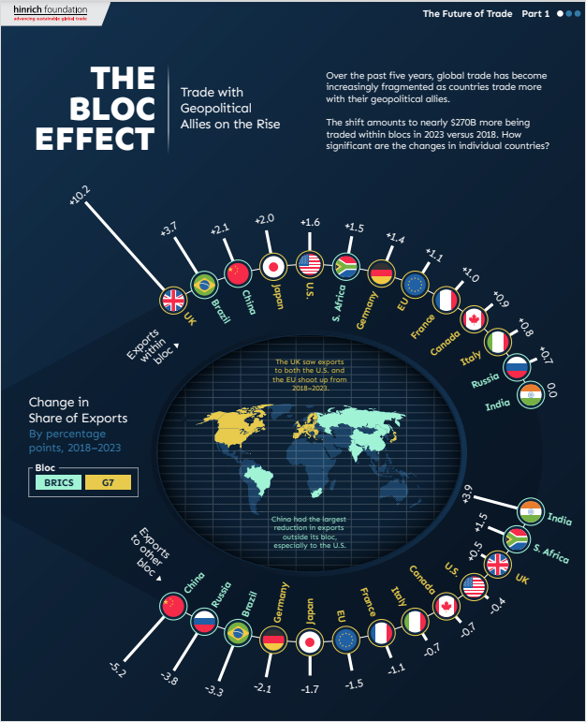

As global geopolitical tensions rise, nations around the world are trading more with those they deem geopolitically allied. The bifurcation isn’t deglobalization, but it is further signs of trade fragmentation that ultimately will stifle productivity, capital allocation, knowledge diffusion, and hit poorer developing economies most heavily. Visual Capitalist shows how the bloc effect is taking shape.

(Text by Chuin Wei Yap)

In December last year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) began stepping up warnings that the rising fragmentation of global trade is bringing the world to the brink of a new Cold War.

The pandemic, war in Europe, and geopolitical tensions between the two largest economies of the world are driving the changes. In China, the call is for “self-reliance.” In the US and Europe, leaders are moving to “de-risk.”

The consequences are manifest in a new graphic from Visual Capitalist and the Hinrich Foundation, based on analysis of data from the IMF and UN Trade and Development.

Over the past five years, the data show, nations are trading more and more with their geopolitical allies. The shift amounts to nearly US$270 billion diverted to trade within blocs in 2023 compared with 2018.

In this reconfiguration of global trade, China posted the largest reduction in exports outside its bloc, especially in exports to the US. Russia was next, cutting its commercial ties with those outside its bloc by nearly 4% in the same period. Similar trends occurred across the West.

There are outliers. India posted the largest increase in exports outside its bloc, up by 4%. This underpins geoeconomic developments to which New Delhi has responded by effectively pivoting from being “non-aligned” to “multi-aligned.” South Africa also exported to a greater diversity of non-bloc partners, up 1.5% between 2018 and 2023, Visual Capitalist showed.

The approximations for blocs are based on economies that belong to the BRICS grouping led by Russia and China, and to the Group of Seven as a proxy for the Western bloc. But the geopolitical trend extends beyond these two groupings. As UN Trade and Development data shows, bilateral trade within geopolitically close dyads is up 6% from the start of 2022 to the present. Trade between nations that aren’t geopolitically close fell by roughly the same magnitude in the period.

This isn’t to say that deglobalization is happening. At the intermediate goods level – trade in componentry that makes up global supply chains – trade is not falling so much as it is reorganizing, as our earlier research commissioned by Oxford Economics has shown.

“We do not see meaningful deglobalization, as the share of global trade in world GDP remains relatively stable,” the IMF’s Gita Gopinath said. “But we are beginning to see signs of fragmentation with meaningful shifts in underlying bilateral trading relations.…The capacity of trade to incentivize within-industry reallocation and generate productivity gains would be stifled. Less trade would also imply less knowledge diffusion, a key benefit of integration, which could also be reduced by fragmentation of cross-border direct investment.”

These costs would weigh disproportionately on developing countries, she warned.

The morphing of supply chains is driving a bloc effect. De-risking has its consequences.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).